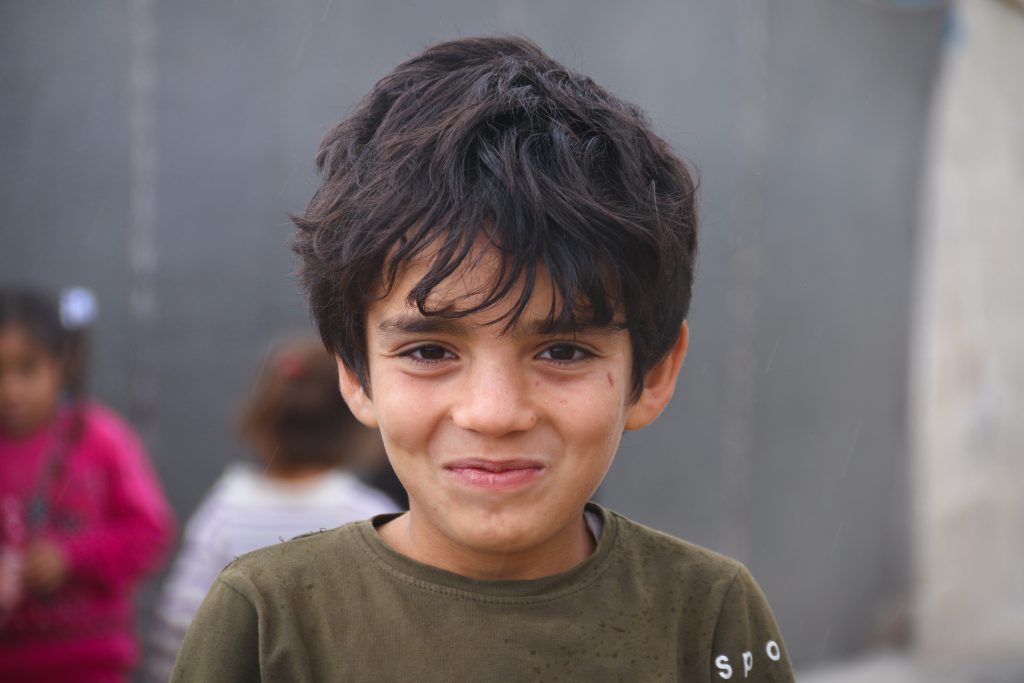

It is impossible to know how many child refugees embark on journeys in search of asylum. However, we know that almost 40% of child refugees who arrive in the EU do so unaccompanied (UNICEF, 2020). We also know some of the hostile environments which they face: mountains, deserts, war-torn regions and deadly sea crossings hijacked by criminal gangs. A recent case in the High Court, however, has shone a light on the hostile legal environment which child refugees have also had to face over recent years upon arrival in the UK.

The Dublin III Regulation

In 1990, the EU Member States agreed on a common procedure for allocating responsibility in relation to asylum claims, which has since been replaced by the Dublin III Regulation (604/2013). But the core principle remains the same: asylum claims should be processed in the Member State where the application was made (Home Office, 2020).

The Dublin III Regulation also establishes the procedure for reuniting child refugees with their parent(s) or relatives who arrive in a different Member State. Article 8 allocates responsibility to the Member State where the relative(s) has applied for asylum. It is for the Member State in which the child arrives to request the transfer (known as ‘Dublin transfers’); articles 21 and 22 provide ambitious deadlines for handling these requests and reuniting families (Home Office, 2020).

Article 6 of the Dublin III Regulation suggests that the purpose of the scheme is to protect the ‘best interests of the child’ (Home Office, 2020). However, if this is true, as will usually be the case, why don’t Member States volunteer to take responsibility for the child’s family?

This is allowed under Dublin III. It’s known as the derogation procedure (Article 17) (Home Office, 2020). The best example of it being used is Germany’s open invitation to refugees fleeing war in Syria after entry into Serbia and Hungary had been blocked in 2015 (Right To Remain, 2015).

But the derogation procedure is an exception to the rule. Instead, the Member States seem to be more interested in deterring refugees, both through housing conditions (BBC, 2021) and indefinite detention (Right To Remain, n.d.). Such policies create hostile environments for refugees. This can be seen from the case of Safe Passage v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021] EWHC 1821 in which the Home Office had adopted an approach to the implementation of Dublin III so hostile that the High Court declared aspects of it to be unlawful.

Dublin III in the UK

Safe Passage v Secretary of State for the Home Department revolves around the question of whether Home Office guidance on Dublin III was compatible with the Regulation. The Home Office produced guidance for caseworkers in April 2020 which was updated in December so as to make provisions until the end of the UK-EU Transition Period. Those provisions guaranteed that requests for transfer made before the end of the Transition Period would be concluded irrespective of UK membership.

The High Court identified two aspects of this guidance as being incompatible with the Dublin III Regulation. The first relates to the guidance published in April 2020; it concerns advice for local authorities to ‘undertake an assessment with the family or relative(s) once the family link has been established’ (High Court, 2021). But this is what Dingemans LJ said: ‘This advice established a bright line that the local authority should not undertake an assessment with the family or relative until the family link has been established’ (High Court, 2021). Instead, the High Court held that local authorities can play an important role in assessing the best interests of the child and should therefore be involved as soon as possible.

The second aspect which the High Court found to be unlawful is found in each version of the guidance, and is a shocking provision which reveals hostile assumptions at the heart of the Home Office approach.

Article 22 of Dublin III gives member states a period of two months to respond to each request for transfer. However, when the two month period is ‘drawing to a close’, and, for whatever reason, it has not been possible to establish whether a family link exists or what is in the best interests of the child, the Home Office advises caseworks to reject the request. The High Court suggests the Home Office should have deployed more resources: ‘member states were required to provide sufficient resources to discharge their obligations’ (High Court, 2021). But this guidance implies that the true priority of the Home Office was to avoid default acceptances rather than to safeguard vulnerable children.

Does the High Court go far enough?

The High Court refused to hold all provisions under dispute to be unlawful. In particular, Safe Passage drew attention to guidance about the ‘onus’ or burden of proof. The Home Office advice said this: ‘The onus is on the applicant and their qualifying family member, sibling, relative or relations […] in the UK to prove their relationship’ (High Court, 2021). But this advice contradicts Article 6(4) of the Regulation which instructs the Member State to ‘take appropriate action to identify family members’ across the EU territory.

The High Court chose not to hold this provision unlawful. Instead, the Court pointed to other elements of the advice which told caseworkers to consider ‘evidence submitted by the requesting State’ and ‘information contained in Home Office records’ (High Court, 2021). But how fair is this? And is it even consistent within the judgment? The High Court has already held the April 2020 guidance unlawful because it established ‘a bright line’ in contempt of the Dublin III Regulation, but doesn’t this also create a bright line, clear and wrong in equal measure?

Child refugees after Brexit

The High Court chose not to quash the Home Office guidance; the Court pointed instead to ‘substantial parts of the policy guidance which are not erroneous in law’ (High Court, 2021). The guidance therefore remains in force for outstanding asylum applications and requests for transfer which are made before the end of 2021.

In 2021, a record number of 28,300 migrants are estimated to have crossed the English Channel (Drummond, 2022). How many were unaccompanied children? How many were the parents and siblings of unaccompanied children elsewhere in Europe? It has become clear that there will be no post-Brexit replica of Dublin III through bilateral agreements (Bulman, 2021; ECRE, 2021). But it remains unclear how the UK Government and EU Member States plan to reunite child refugees and their parents.

Humanium is one of many organisations working to raise awareness of these issues and advocate in favour of their resolution. We support child refugees who are seeking asylum not only in the UK but also around the world, and will continue to do so, in the hope of helping to create a world where children are not forced to leave their parents, and their homes. You can support us on this important mission in several ways, such as making a donation, volunteering, becoming a member, and sponsoring a child.

Written by Patrick Naylor

References:

BBC, (2021) ‘Napier Barracks: Housing migrants at barracks unlawful, court rules’ [News]. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-kent-57335499, accessed on 27 March 2022.

Bulman, M., (2021) ‘EU countries rule out asylum deals in blow to Priti Patel’s immigration plans’ [Article]. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/asylum-eu-deportation-home-office-b1836598.html, accessed on 27 March 2022.

Drummond, M., (2022) ‘Record year sees more than 28,300 people cross English Channel to the UK’ [Article]. Retrieved from: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/government-english-channel-people-france-home-office-b1986159.html, accessed on 27 March 2022.

ECRE, (2021) ‘UK: Patel plan going nowhere fast, MPs demanding removal of Home Office oversight of asylum housing, new condemnation of Home Office over asylum barracks’ [Article]. Retrieved from: https://ecre.org/uk-patel-plan-going-nowhere-fast-mps-demanding-removal-of-home-office-oversight-of-asylum-housing-new-condemnation-of-home-office-over-asylum-barracks/, accessed on 27 March 2022.

High Court, (2021) ‘Safe Passage International v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2021] EWHC 1821 (Admin)’ [Judgment]. Retrieved from: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Safe-Passage-v-SSHD.pdf, accessed on 27 March 2022.

Home Office, (2020) ‘Dublin III Regulation: Version 4.0’ [Policy guidance]. Retrieved from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/909412/dublin-III-regulation.pdf, accessed on 27 March 2022.

Right To Remain, (2015) ‘Germany’s suspension of the Dublin Protocol’ [News]. Retrieved from: https://righttoremain.org.uk/germanys-suspension-of-the-dublin-protocol-a-welcome-display-of-european-and-global-solidarity/, accessed on 27 March 2022.

Right To Remain, (n.d.) ‘Immigration Detention’ [Article]. Retrieved from: https://righttoremain.org.uk/toolkit/detention/, accessed on 27 March 2022.

UNICEF, (2020) ‘Latest statistics and graphics on refugee and migrant children’ [Statistics]. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/eca/emergencies/latest-statistics-and-graphics-refugee-and-migrant-children, accessed on 27 March 2022.